Evacuation

The evacuation of children in Britain began just before war officially broke out in Britain on 3 September 1939. It was imperative to the government that the children were kept safe and were sent to safer, lower risk areas within the country, and even outside of the country to places like America, Australia, and Canada.

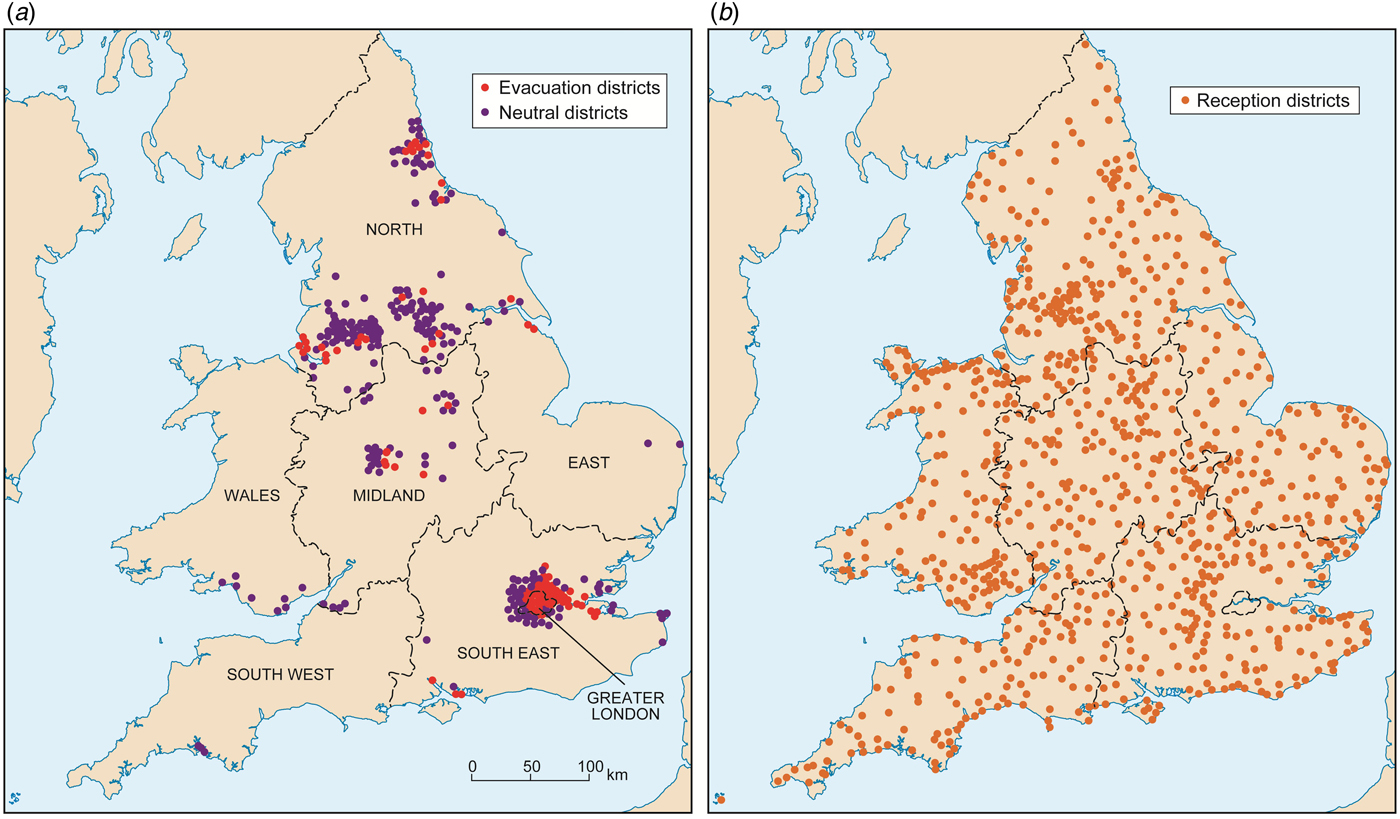

In July 1939, households in Britain all recieved a leaflet on the details about evacuation. Within this was a list of evacuated areas;

- London and the County Boroughs of West Ham and East Ham.

- The Medway towns of Chatham, Gillingham and Rochester.

- Portsmouth, Gosport, and Southampton.

- Birmingham and Smethwick.

- Liverpool, Bootle, Birkenhed and Wallasey.

- Manchester and Salford.

- Sheffield, Leeds, Bradford and Hull.

- Newcastle and Gateshead.

- Edinburgh, Rosyth, Glasglow, Clydebank and Dundee.

1 September 1939 saw the first wave of the evacuation process, also known as Operation Pied Piper. During this, around 1.5 million people were sent to safer areas than where they lived and most likely grew up in. Sadly, not all of these people chose to stay in their relocated areas, and by January 1940 around 60% had returned home. This was due to what was to be called the Phoney War. Not much was happening during these 8 months; no bombs were dropped and not much fighting was taking place. Therefore prompting people to return to the comfort of their own homes.

June 1940 saw the second wave of evacuation. Here, around 100,000 children were again evacuated. This included some that had returned only months before in the January. September of the same year was the month the Blitz began over Britain. For the safety of the British people, particularly the children, more were evacuated from the dangers and the targets of their cities.June 1944 saw the third, and final, wave of evacuation. Although the war was well into the years at this point, and the Blitz was over, London was experiencing yet another bombing campaigned launched against them by the Germans. The V1 and the V2 rocket became the focus weapon used by the Germans to try and defeat Britain. During this wave, 1,000,000 vunerable people were evacuated to safety from this new form of attack.

So, how was the evacuation process carried out? It relied on volunteers ranging from the Women's Voluntary Service to teachers to local authority officials, and more. They helped with the children, as well as the likes of providing refreshments in the billeting halls and helping to house the children in their new evacuated areas.

Parents of these children were given a list to instruct them on what the children could take with them when they were sent to their temporary new homes. The Imperial War Museum states that this included:

- A gas mask (which was a requirement)

- A change of underclothes

- Night clothes

- Pimsoll

- Spare stockings or socks

- Toothbrush

- Comb

- Towel

- Soap

- Face cloth

- Handkerchiefs

- Warm coat

Initially, most households were expected to take on one child. However, with the large number being sent to these safe areas, it meant that some ended up with up to three times the amount than what they first thought. Those billiters recieved a sum of money to help pay for the children they had taken in; this was to cover board, lodging and all other expenses that would occur for looking after an unaccompanied child. If the household only had on child, this sum would have been 10s. 6d and for more than one child it would have been 8s. 6d each. For the child accompanied by their mother, the sum would have been 5s. a week for the adult and 3s. a week for the child.

For the majority, the initial view of these evacuees was unhappiness. Those from the countryside often saw these children as rough, due to many having arrived from poorer cities where they did not have much; many arrived to their new homes with very little belongings as their parents struggled to provide the items listed due to this urban poverty. Thin, sickly looking children (many with headlice) were frowned upon by their new host towns.

Whilst many children had a positive

experience of being evacuated and got to experience many new things they

would have never in the city, this was not always the case for all.

There were many children who had bad experiences, with families who were

not the nicest to them which prompted many to run away and to

return back to their homes in the cities. Some of these children were used for manual labour, either within the house of the farm. Cases also show beatings inflicted upon the evacuees by their host families, and the poor treatment inflicted upon them that included little food. Not all, but some of these host families would also take the money and rations that was meant for their billeted children's upkeep, meaning they were treat in an ill manner and often went with very little food. This ill manner was not just held by those who had taken them in, in some cases it also spread to the local community as they were resented by those who lived there. Furthermore, it was a struggle for many to adapt to living in the countryside as opposed to the city life that they were used to. They had to get used to living a life that was without electricity, gas or running water, and had many new smells that they were not acustomed to.

On the other hand, many children experienced a happy few years in the countryside, with many not wanting to return home. Love and affection was given to those children, and they were able to make friends. They were fed and housed well and there was the ability to learn about farm animals (many did not know what a cow was prior to being evacuated), some families taught them how to make bread, took them to the pictures, and overall host families provided love and a warm, welcoming experience for those that they took in during the war years.

As can be seen, not all children experienced the same warm reception and love that others did. Some were treated unfairly, and were beaten, whereas others had the years of their lives and either remained in the countryside, or found leaving their "foster homes" very difficult.

The evacuation movement was one that was made to protect the children of Britain and to reduce the devastation that the government knew was coming with the impending bombing raids from Germany. The biggest, and most concentrated, movement of people in the history of Britain was one of neccessity. Millions were evacuated between 1939 to 1944, and yet many returned home prematurely. It was a success, and it was a failure. Many children were left with wonderful memories, others were left with awful ones that scarred them for the rest of their lives. It put together two different aspects of British life; the urban and the rural. It presented new opportunities and experiences for both as it put together two very different groups of people; ones that had experienced life in pre-war Britain very differently.

The evacuation process is a movement of history that will not easily be forgotten. It played a huge part in Wartime history, as well as British history. This mass movement of young children, their parents and teachers, is one that will be remembered.

To read more about the stories of children during the war, click here.

Comments

Post a Comment